Program Synthesis

Introduction

The gist of it is generating programs symbolically instead of using a neural network. It is a completely different approach to program generation and comes with different trade-offs.

There is no hallucination, no syntax errors and guaranteed to be type correct if you want. You can give it a library for it to use, give any kind of hint or constraint. This could be assertions like assert f(2) = 4 or assert f(x) = IsPrime(x) for all inputs x. You can say “only use 100 steps to calculate the result” or “only use 100 bytes of memory.”

A Simple Implementation

We can enumerate every program until you find the “correct” one. You can define correctness however you want.

One way is to encode a specification. Here’s an example:

method Max(a: int, b: int): int

ensures Max(a, b) >= a && Max(a, b) >= b

ensures Max(a, b) == a || Max(a, b) == b

{

TODO()

}

ensures Max(a, b) >= a && Max(a, b) >= b tells us that the return value must be greater than or equal to both a and b. ensures Max(a, b) == a || Max(a, b) == b specifies that the result must either be a or b. If we didn’t have the first condition, just returning a would be correct; and a + b would be correct if we didn’t have the second condition.

Another option is to provide examples:

assert Max(1, 2) == 2

assert Max(-1, 0) == 0

I like this one better. It’s much easier than doing formal reasoning. It feels more interactive. This video is a fantastic demo of what I mean. In it, the presenter tries to synthesize a program to extract users’ first and last names from emails.

It is not either or. We can run the type checker and run it against the examples. Victor Taelin’s SupGen uses both approaches. There’s also Smyth, which has interactive examples on their website you can play with. I think they’re planning on integrating it into the Hazel programming language. I highly recommend checking it out as well.

Although their mechanism doesn’t look like our brains at all, they generalize well from small number of examples. AIs that generalize well and interpretable might look like these instead of deep neural networks.

How do we enumerate programs?

Enumerating Programs

Let’s simplify the problem as much as possible but not too much, as we want to capture the essential complexity. The following language seems like a perfect candidate:

expr =

| 0

| S(expr)

| expr * expr

It has natural numbers. Represented as in Peano arithmetic. S(0) represents 1, S(S(0)) represents 2, etc. We also have multiplication expressions because otherwise, we could just enumerate like 0, S(0), S(S(0)), ... and that’s not interesting at all. With multiplication however, simply enumerating like that won’t work because we’d never generate expressions like 0 * S(0). In a sense, we have to be fair to each expression type, sometimes generating one type and sometimes another.

So we have a search problem where:

- We have to make a decision at each step e.g. after

S(0) * 0what’s the next expression? - There is a hierarchy between things we search for. Every

S(expr * expr)is aS(expr)and that in turn is anexpr.

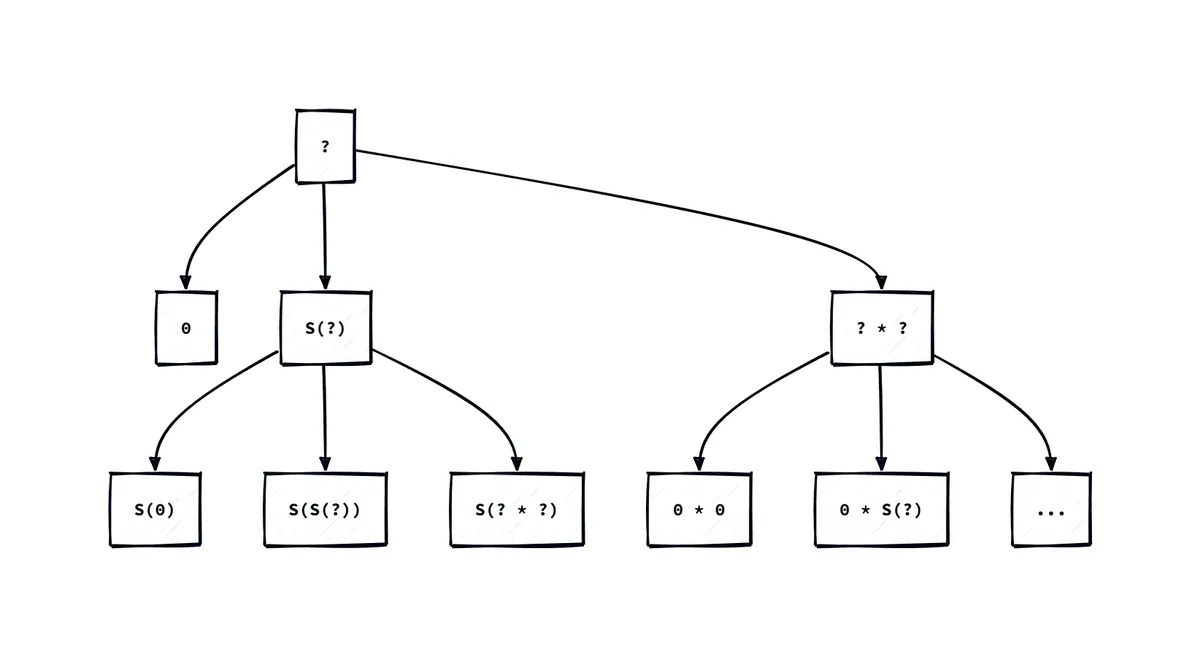

A tree structure is ideal for visualizing this problem. Now, you might be wondering, how should we connect the nodes? And what should be the root? The grammar already tells us. expr is the root. 0, S(expr), expr * expr are the children. S(0), S(expr), S(expr * expr) are the children of S(expr) and so on.

expr is like TODO expressions. It’s a placeholder for any expression. Smyth calls these holes and represent them with ??. I’ll use ? instead.

Here’s a visualization:

It mirrors the grammar. Everywhere we see a ?, we replace it with 0, S(?), and ? * ?. It also looks like we’re pattern matching against the program and becoming more specific at each level:

match x {

0 => ..

S(y) => match y {

S(0) => ..

S(S(z)) => ..

S(Mul(z, k)) => ..

}

Mul(y, z) => match (y, z) {

(0, 0) => ..

(0, S(k)) => ..

..

}

}

As you can see, the depth of this tree is infinite, so we can’t really use DFS. BFS is perfect for this use case because it explores the tree level by level. Since the programs grow from short to long, if there is a simpler correct program, we’ll find it first.

Implementing It in Code

Let’s first just scaffold the BFS algorithm:

function enumerate(program) {

const queue = [program];

while (queue.length !== 0) {

const expr = queue.shift();

console.log(showExpression(expr));

//TODO: find the children and add them to the queue

}

}

There’s nothing new here; we start our queue with the root and print the nodes in the queue until it’s empty. The crux of the algorithm is finding the children of a node. Let’s define an expand function that, given a node, replaces each hole with possible expression types as we discussed earlier.

// Define helpers to construct the expressions so that it's not crowded.

const hole = () => ({ type: "hole" });

const O = () => ({ type: "zero" });

const S = (prev) => ({ type: "succ", prev });

const mul = (left, right) => ({

type: "mul",

left,

right,

});

function expand(expr) {

switch (expr.type) {

case "zero":

return [];

case "hole":

// [0, S(?), ? * ?]

return [O(), S(hole()), mul(hole(), hole())];

}

}

Alright, those first two cases – zero and hole – were pretty straightforward. But now we get to the other two: succ and mul. Things start to get a little trickier here because these expressions can balloon in complexity. We could have something like S(S(S(S(?)))) or (? * 0) * (0 * S(?)). Now, one way to handle this would be to just walk through the expression, the AST, and replace any ? we find. But that sounds quite hard because we need to copy the tree for every replacement Since we’re already dealing with a tree structure, a more natural approach is to use recursion. We can simply call our expand function on each part of the expression. This way, we’ll eventually hit those base cases we already coded up. Let’s see how this works with S(S(?)) as an example:

expand(S(S(?))

|

expand(S(?))

|

expand(?) == [0, S(?), ? * ?]

Now we do the reverse: we take these basic expressions and construct our original expression. In this case, we wrap each of those expressions with S:

[0, S(?), ? * ?]

|

[S(0), S(S(?)), S(? * ?)]

|

[S(S(0)), S(S(S(?))), S(S(? * ?))]

Translating this into code:

function expand(expr) {

switch (expr.type) {

case "zero":

return [];

case "hole":

// [0, S(?), ? * ?]

return [O(), S(hole()), mul(hole(), hole())];

+ case "succ": {

+ const result = [];

+ for(const prev of expand(expr.prev)) {

+ result.push(S(prev))

+ }

+ return result;

}

}

}

This is just a map operation so we could do it more succinctly like this:

function expand(expr) {

switch (expr.type) {

case "zero":

return [];

case "hole":

// [0, S(?), ? * ?]

return [O(), S(hole()), mul(hole(), hole())];

+ case "succ": {

+ return expand(expr.prev).map(S);

+ }

}

}

? * ? expression is the same but since we have two sub-expressions, we have nested for loops:

function expand(expr) {

switch (expr.type) {

case "zero":

return [];

case "hole":

// [0, S(?), ? * ?]

return [O(), S(hole()), mul(hole(), hole())];

case "succ": {

return expand(expr.prev).map(S);

}

+ case "mul": {

+ const result = [];

+ for (const left of expand(expr.left)) {

+ for (const right of expand(expr.right)) {

+ result.push(mul(left, right));

+ }

+ }

+ return result;

+ }

}

}

Now we can use this to find the children in our enumerate function:

function enumerate(program) {

const queue = [program];

while (queue.length !== 0) {

const expr = queue.shift();

console.log(showExpression(expr));

for (const child of expand(expr)) {

queue.push(child);

}

}

}

and lastly the showExpression function:

function showExpression(expr: Expression): string {

switch (expr.type) {

case "hole":

return "?";

case "zero":

return "0";

case "succ":

return `S(${showExpression(expr.prev)})`;

case "mul":

return `(${showExpression(expr.left)} * ${showExpression(expr.right)})`;

}

}

If you run enumerate function, it’ll output as follows:

?

0

S(?)

(? * ?)

S(0)

S(S(?))

S((? * ?))

(0 * 0)

(0 * S(?))

(0 * (? * ?))

... and so on

If you look at the tree again, you’ll notice that only the complete nodes are actual programs. To print only those, we can track that information in the queue:

function enumerate(program: Expression) {

- const queue = [program];

+ const queue = [["incomplete", program]];

while (queue.length !== 0) {

- const expr = queue.shift()!;

- console.log(showExpression(expr));

+ const [type, expr] = queue.shift()!;

+ if (type === "complete") {

+ console.log(showExpression(expr));

+ }

for (const [i, child] of expand(expr).entries()) {

// Mark it as complete if it's the first child.

+ const type = i === 0 ? "complete" : "incomplete";

queue.push([type, child]);

}

}

}

Now we only get complete programs:

0

S(0)

(0 * 0)

S(S(0))

S((0 * 0))

(S(0) * S(0))

(S(0) * (0 * 0))

((0 * 0) * S(0))

((0 * 0) * (0 * 0))

S(S(S(0)))

...and so on

Although it’s a nice and short solution, its memory consumption grows exponentially. I don’t know a way to get around that. Another solution would be storing the generated programs in an array and building the next program using their combinations. For example:

0

S(0), 0 * 0

S(S(0)), S(0 * 0), 0 * S(0), 0 * (0 * 0), S(0) * 0, ...

...and so on

We don’t generate incomplete programs, but the growth is still exponential. However, with type information and examples, we’ll be able to prune most of the branches because the number of incorrect implementations is much larger than the number of correct ones.

Conclusion

Of course, this is just the beginning. The language we’ve built here is super simplified – not quite ready to tackle anything truly practical and it doesn’t find any programs. It just enumerates them. But that’s about as far as my current knowledge goes. I’ll write another blog post after I further my understanding.